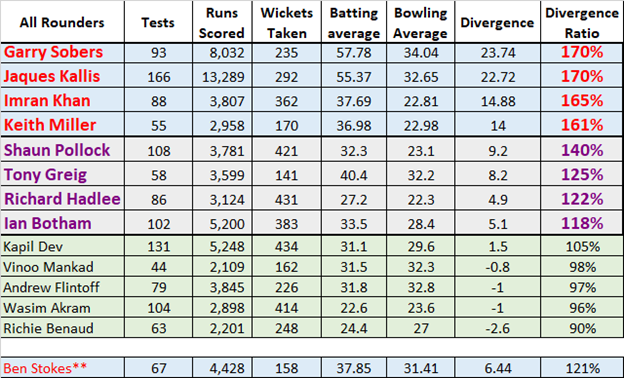

The Great All-Rounders

All-rounders in cricket are a rare breed. It’s hard enough to master one particular skill at test level. To master two at a level that changes the game’s complexion is absolutely masterful. There have been some great all-rounders in the history of the game and there have been many who though not in the same league, have ended up contributing significantly more than a one dimensional player over fairly long periods.

The key metric is the

relationship between the batting averages and the bowling averages. There are

two ways of computing this –a) arithmetic difference b) ratio. I prefer the

ratio, mainly because the plain difference doesn’t do justice to the bowling

skills.

For example, take someone

averaging 30 with the ball and 33 with the bat, and compare him with someone

averaging 23 with the ball and 26 with the bat. The second player is far more

devastating with the bat, and the first one in spite of being a better batsman,

is not likely to be commanding his place in the side on batting alone either.

Players with very high batting average (say 50) can’t really be classified as

all-rounders if their bowling average is 45 or 47. No captain will give him the

ball.

Note: Stokes is a current player and one

can see that he clearly belongs in this club. He could get better or may slip a

bit, but he’s unlikely to drop out of reckoning.

Players with a ratio of 50-80% can really be called “bits and pieces”. However, at that level too, the bits and the pieces sum up to more than one. They are often more valuable in the long run than a pure specialist. Players with a lower ratio (below 50%) shouldn’t be termed as all-rounders. After all, if someone is averaging 30 or less with the ball an average of 15-16 with the bat hardly qualifies as a dependable batsman. Similarly, if someone is averaging 30 or more with the bat, he is hardly likely to get a call from his captain if his bowling average is over 50. At best he will come in sometimes as a relief bowler or a surprise change.

Typical bits and pieces men would be men

like Madan Lal (average 22.65 with the bat and 40 with the ball), Roger Binny

(average 32 with the ball and 23 with the bat). They were useful, but valuable

only in certain specific conditions.

Let’s look at the elite group a little more

closely. It is evident that the benchmarks that they have set are pretty tough

for anyone to reach. I have divided their careers into three roughly equal

phases to see how they progressed.

Garry Sobers:

Sobers did not start out as a frontline bowler. However, during his 2nd phase he developed into a pretty potent bowler and took 125 wickets in 33 tests at an average of under 28. During this phase, his divergence score was 227% The batting quality was such that for much of his career he was averaging well over 60. Sobers’ last phase was a disappointing phase where both his bowling and batting dropped considerably. His career progression looks like this –

Once Sobers discovered his bowling mojo his divergence score

(on a cumulative basis) quickly shot past 150% and never dropped below it. He

finally finished with a divergence score 170.

Jaques Kallis:

Unlike Sobers, Kallis started off with great bowling form.

In his case, it’s the batting that took longer to reach great heights. Kallis’ phase

1 is longer (56 tests) and he was at least 13-14 points behind Sobers in the

batting averages. However, his bowling was a significant level above Sobers’ in

his first phase. Hs second phase, like Sobers, was his best. His batting never

slipped throughout his career, though the bowling waned considerably. What is

clear from the top two performers is that it’s impossible to keep up a high

level of performance in both aspects of the game in the high pressure

environment of Test cricket.

The two have set benchmarks for all time.

Of the two, Sobers was the more flamboyant and charismatic.

It’s impossible to apply the sobriquet charismatic on Kallis. He was always the

efficient professional and never a candidate for leadership. Sobers, on the

other hand was a leader of men and commanded loyalty. He also brought in the

crowds. His cricketing calendar was packed as he was a regular in the English

county cricket and played for South Australia fairly regularly in the

Australian domestic season. He was as good an athlete as any in the world, and

had few peers on the cricket field.

While the first two on the elite list where more batsmen

than bowlers, the next two were more bowlers than batsmen. They were the main

strike bowlers for their respective sides and their bowling was so good that it

completely overshadowed their batting prowess. They were exceptionally good

with the bat. Much more than people noticed.

Imran Khan:

Imran debuted during the seventies when Pakistan wasn’t

playing too much of test cricket. In his first phase there were three years

(1972, 1973, and 1975) when he had no test cricket at all. The next 5 years saw

the emergence of Imran as a world class fast bowler with a striking capability

as good as any in the world. It all started with the Sydney test in Australia

in 1976.

It was only in the second phase of his career that he

emerged as a very dependable and capable batsman in the lower order. He also

became the captain of his side and proved to be one of the great leaders in the

history of cricket. His bowling also peaked during this period and his

divergence ratio rivalled Sobers. 151 wickets at around 16 each was a world

beating performance in the era of fearsome fast bowlers from the West Indies.

No one thought at that time that his batting would improve

further. Not only did it improve, it reached dizzying levels, as he averaged

nearly 60 in his last 28 tests. The bowling never flagged as he took 113

wickets during this period. Imran Khan’s trajectory is different from Sobers

and Kallis. It is a continuous improvement graph. A very rare thing. Kapil Dev

recently said that Imran was the hardest working cricketer he knew, and the

figures corroborate the observation.

Keith Miller:

Miller is different from everyone else for one simple

reason. The younger days of his life were taken away by the war and he was well

into his mid-twenties by the time he made his debut. He was among the fastest

of his generation and made the batsmen duck and weave. A flamboyant larger than

life character, he was a great crowd puller. In all this, he was always a solid

dependent bat, who could also tear apart any bowling when in the mood. Since he

is from the pre-television era, few people in India even remember him. But in

Australia he continues to be a legend. Not the least because of his duels with

Bradman while playing for Victoria in the domestic matches in Australia.

Miller was so good as an all-rounder that his divergence

scores were high throughout his career. In fact it was at the bottom when he

finished at very high score of 161%. His bowling was always top drawer, right

through his career. It was only the batting which started flagging a bit

towards the end.

In this post, I am not looking at the others in detail. It

would be too long a post. However, the phase wise break down clearly suggests

that they were in the elite during at least one phase of their careers. In any

case the second band is quite exceptional. It’s just that the elite group

creates a band of its own.

Ben Stokes is still an active cricketer, and it would be

interesting to see where he ends up.

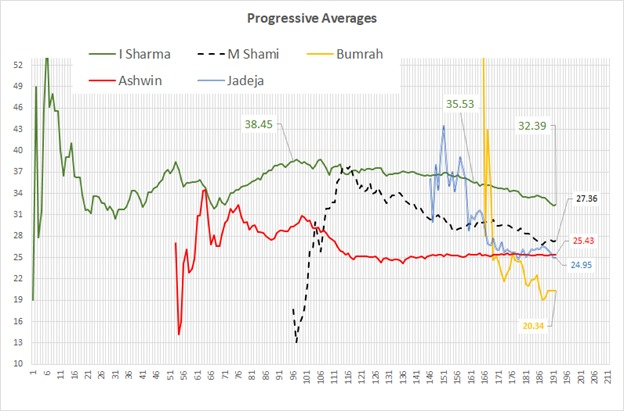

The graph below tracks the progressive divergence of 6 of

these all-rounders. The only reason why I have limited it to 6 is that the

graph would get too cluttered.

It is interesting to note that someone had to play more

tests than Miller to get past him.

The other great all-rounders and their phase-wise performance is given below. They were all outstanding and some of them had at phases that were at par with the elite club.

Comments

Post a Comment