Sovereign Wealth Funds and their Impact - Part 2

Part 2 - The story

of the Norwegian SWF and The SWF of China

"With a good

perspective on history, we can have a better understanding of the past and present,

and thus a clear vision of the future." — Carlos Slim Helu

The Norway Story

The Sovereign Wealth Fund of

Norway is one of the largest and the most talked about. The story of its

evolution gives valuable insights on institution building. It wasn’t built in

one day as a masterstroke. Rather, processes were put in motion which played

out over a couple of decades. It continues to evolve and has a high level of

stakeholder participation.

When oil production started

in Norway in the early 1970s, the government there was aware of the risks to

the domestic economy. The oil shock of the seventies also occurred then. Unlike

the Persian Gulf states, Norway already was a developed economy without oil. It

was also known that the oil reserves would not last more than 50 years.

Therefore, from an early stage, the government worked to find measures that

would allow the sustainable and long-term management of petroleum assets and

revenues, creating wealth that would outlive the period of oil production.

Norway established a

sovereign wealth fund in 1990 – the Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG). The

fund has enabled the government to manage oil assets and revenues sustainably while saving and creating wealth for future generations. Fiscal policy and

investment guidelines have continued to develop over the years. Today, Norway’s

GPFG is the largest such fund in the world.

The key difference of GPFG

with other similar funds is that it effectively converts oil assets into an

investment portfolio, allowing systematic management of the funds, and to

live off the returns of the investment rather than the common practice of

spending on the asset itself. It also meant that Norway did not subsidize the

oil consumption of its own citizens.

Timelines –

In 1969, one of the world’s

largest offshore oilfields was discovered off Norway. Suddenly the country had

a lot of oil to sell, and the country’s economy grew dramatically. It was

decided early on that revenue from oil and gas should be used cautiously in

order to avoid imbalances in the economy. In 1990, the Norwegian parliament

passed legislation to support this, creating what is now the Government Pension

Fund Global, and the first money was deposited in the fund in 1996. It was decided

that the fund should only be invested abroad. In other words, the exercise was

a diversification away from the economy of Norway itself.

The basic rule and guiding

philosophy

Each year, the Norwegian

government can spend only a small part of the fund, and this still amounts to

almost 20 percent of the government budget. There is a broad political

consensus on how the fund should be managed. The less spent today, the better

the position the country will be in to deal with downturns and crises in the

future. Budget surpluses are transferred to the fund, while deficits are

covered with money from the fund. Thus, the country can spend more in hard

times and less in good times. So that the fund benefits as many people as

possible in the future too, politicians have agreed on a fiscal rule which ensures

that the country does not spend more than the expected return on the fund. On

average, the government is to spend only the equivalent of the real return on

the fund, which is estimated to be around 3 percent per year. In this way, oil

revenue is phased only gradually into the economy. At the same time, only the

return on the fund is spent, and not the fund’s capital.

From an ownership

perspective, natural resources are viewed as assets that belong to the public.

In this scenario, politicians acting as trustees for the public should make

sure the asset values are managed sustainably so that future generations can

also benefit from the revenue generated by these assets. This philosophy

evolved in a population that was educated and in an economy that had experience

in dealing with natural resources as significant contributors to the economy.

In the case of Norway, before the discovery of oil, there was a historical

tradition of state involvement in economic management and an economic model

that was reliant on natural resources. Apart from fisheries and forestry, the

country had developed industrial capabilities around hydroelectricity which

became useful in the later development of its domestic oil industry. All of

these factors converged in a responsible response to the issue at hand.

As an instrument for

long-term savings, the GPFG’s investment strategy aims to maximize financial

returns at moderate risk in order to secure maximum benefits for future

generations. Compared to similar funds, the GPFG has a higher risk-bearing

capacity because it is not subject to short-term liquidity requirements and has

a long investment horizon.

A lot of background work

The country began structuring

the oil industry in the early 1970s itself. In 1971, the “Ten Oil Commandments”

were formulated to guide the nation’s petroleum policy. One year later, the

state-owned oil company Statoil was created, and the Petroleum Directorate was

established as a separate body to administer natural resources and regulate

safety and work environment issues.

In February 1974 the Ministry

of Finance submitted a white paper, “The role of petroleum activity in

Norwegian society”, explaining how oil wealth should be used to develop a

better society. One of the report’s main arguments was that democratic

institutions should control all aspects of petroleum policy, focusing on

control over the pace of extraction operations. The idea of saving the surplus

abroad was mentioned in the white paper but wasn’t discussed much until the

early eighties. It was then, in 1982, that the Norwegian government established

a committee to review the future of petroleum activities. The idea of a

Norwegian SWF as an instrument for the long-term management of oil revenues was

presented in 1983 by this Committee, consisting of a group of experts appointed

by the government. The committee also proposed investing the fund in

international markets to prevent the overheating of Norway’s economy. This was

an important recommendation, given the size of the economy. The committee’s proposal

entered the political agenda and the idea of the fund continued to mature

during the 1980s. What is important to note is the fact that the whole process

was consultative in nature, involved the entire spectrum of stakeholders, and

took a decade to reach its conclusions.

After all this groundwork had

been laid, the Norwegian SWF was established in 1990 by an act of parliament, the

1990 Government Pension Fund Act. The SWF was initially called the Petroleum

Fund, and in 2006 it was renamed as the Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG) –

as it is known today.

The fund is not a separate

entity but was established as a deposit account at the Central Bank of Norway

where the government deposits petroleum revenue through regular transfers. The

official owner of the GPFG is the Ministry of Finance, acting on behalf of the

Norwegian Parliament, for the Norwegian people. The Ministry of Finance

determines the investment strategy and ethical guidelines of the fund and

monitors operational management. A dedicated asset management team covers

the GPFG portfolio’s daily operations, investing in the fixed-income and equity

markets and – since 2011 – in property, following strict governance guidelines

as well as a strategic benchmark index set by the Norwegian government.

Diversification and Growth

The current holdings are

about 70% equity, 27% fixed income, and 3% Real Estate. The fund returns have

been good over a long period.

Initially, the structure of

the fund was conservative. Although government revenues from oil were being

transferred to the fund, it was observed that the full amount was being

returned to the fiscal budget on an ongoing basis to cover the non-oil deficit.

Economic reforms in the country led to the first net allocation to the fund in

1996.

In 1998, the government set

up Norges Bank Investment Management, an asset management unit to manage the

GPFG on behalf of the Ministry of Finance. That year, the unit invested 40

percent of the fund in equities in order to diversify a portfolio previously

focused on government bonds. The portfolio has continued to diversify ever

since, reaching a market value in 2019 of NOK8,256 billion.

The fund is an active

investor in more than 9,000 companies worldwide. Through its ethical investment

guidelines, the fund promotes good corporate governance standards and

encourages businesses to implement sound environmental and social standards.

As of now, since the time oil production began in Norway in the 1970s, 50 percent of oil reserves have been consumed. It is now estimated that the remaining reserves will last for maybe another 50 years. However, from the first transfer of NOK 1.98 million in 1996, the value of the fund has increased to NOK 8.25 billion, exceeding all expectations of the first 20 years of its existence. Overall, the GPFG has enabled revenues generated from oil to be more sustainable and long-lasting while the value of the asset base was maintained and not just spend.

Other Considerations

These are good examples of

what can evolve from a well-designed consultative process.

In 2005 the Council of Ethics

was set up to make recommendations to the Ministry of Finance and later the

Central Bank regarding ethical investments. Although the exclusion threshold

for these is intentionally set high, companies are assessed based on both their

products and conduct to determine if they represent a risk to the funds’

ethical standards. Based on this information, the fund determines whether

companies should be excluded or placed under observation.

This year the fund excluded five companies, including

commodities trader Glencore, from its holdings after putting a hard limit on

coal-related emissions. The companies excluded during 2019 include Rio

Tinto Plc, Airbus SE, and Japan Tobacco Inc.

Norway’s economy is today of the order

of USD 434 billion. The per capita GDP is USD 81,000, which is among the

highest in the world. For a nation of just 5.3 million inhabitants, this is a

tremendous achievement. The SWF asset is now worth more than USD 1 trillion,

which on a per capita basis is equal to USD 190,000. It is certainly a very

fine cushion for the country which is facing rapid aging. The current age

structure of Norway is

·

0-14 years: 17.96% (male 503,013/female

478,901)

·

15-24 years: 12.02% (male 336,597/female

320,720)

·

25-54 years: 40.75% (male 1,150,762/female

1,077,357)

·

55-64 years: 11.84% (male 328,865/female

318,398)

·

65 years and over: 17.43% (male 442,232/female

510,594)

Thus it has a lot of pensioners and

many more moving into that bracket. However, thanks to the prudence that led to

the creation of the SWF, the country is well placed to meet its welfare needs

should it fall short. The fund is now large and growing, and may even double in

another decade. Already, it is generating USD 50 billion per annum, and it

seems that by the time Norway runs out of oil & gas or voluntarily stops

mining, it will generate of the order of USD 125-150 billion per annum. It’s an

outstanding achievement.

SWF of China

Unlike the Norwegian case, China is more complex in terms of purpose.

The Chinese SWF came into existence only in 2007. However, it is already of

comparable size. China is such a large economy that the SWF is still relatively

small and is likely to grow very quickly in size over the next decade. The

purpose appears to be very different from Norway. It appears to be more of a

strategic entry into very specific sectors. Much literature has been put forth on

the topic to predict the strategic benefits China may be pursuing through its

investments in American firms using its SWF, China Investment Corporation

(CIC). Such speculation lead to inconclusive theories, and often wild

projections. Some of the fears are not entirely unfounded, though most of it

appears to be greatly exaggerated.

Chinese funds benefit from a massive export economy that collects large

holdings of foreign currency that need to be invested. Export-funded sovereign

wealth funds occur in several countries, but the best example is China, where

there are five sovereign wealth funds. Combined, these funds invest trillions

of dollars. China's central bank manages the rest of the government's funds to

regulate its currency. State-run corporations and banks invest in these wealth

funds as well. Each fund has separate goals.

- · China Investment Corp: This fund has roughly USD 950 billion in assets. About 42% of this fund's portfolio was made up of "alternative assets" including real estate, infrastructure, and hedge fund investments. This is the main SWF that we are discussing here.

- · SAFE Investment Company: This fund, with about USD 425 billion in assets under management, incorporates three investment entities based overseas. They include the Investment Company of the People’s Republic of China in Singapore, Gingko Tree in the UK, and Beryl Datura in The British Virgin Islands.

- · Hong Kong Monetary Authority (not exactly China): With over USD 509.4 billion in assets, this fund invests in the Hang Seng stock market and supports the financial stability of Hong Kong.

- · China's National Social Security Fund: This fund currently manages over USD 450 billion in assets. It manages funds recovered from state-owned businesses and other government investment proceeds. It invests mostly in China. Thus, this doesn’t impact international markets significantly.

- · China-Africa Development Fund: This fund manages USD 5 billion8 worth of assets, all of which are intended to "promote the development of Sino-African commercial ties". This is a nascent fund which may grow significantly in future

The China Investment Corporation is China's sovereign wealth fund.

The CIC was created in 2007 to diversify the country's foreign-exchange

holdings. The CIC has since become the world's second-largest sovereign wealth

fund, with nearly $1 trillion in assets under management and major investments

around the globe. In many circles in the west, this is seen as a threat,

although there is no direct evidence of any threat. The feeling is that China

would use it to buy into firms with cutting-edge technology and “steal” IP.

This is an alarmist view.

Structures, Purpose and Western Suspicion

Some researchers have concluded that “The development of the

Chinese sovereign wealth fund reflects China's growing power as well as a shift

in the international order, in which the interaction between the state and

others has changed. In fact, it appears China is using CIC as a way to engage further

within the international financial system as it comes to recognize that its

power stems from domestic economic growth. This seems to mirror the global

trend towards a politicized economy or political capitalism”. This sort of

conclusion is derived from the nature of the investments that CIC has made over

the years.

With a starting capital fund of $200 billion, CIC's approach to

SWF was at a scale radically different from others. Again, this is not a

surprise given the size of China’s economy. By 2010 China reported that it held

$2.65 trillion in US foreign exchange, the highest citing ever. Holding this

much forex was a problem with no international precedence. There is an

opportunity cost associated with this sort of value. The increase of forex holdings

started to reduce its value as they put upward pressure on the exchange rate

of Yuan. By some estimates, it was costing China USD 100 billion a year to keep

its currency from appreciating.

Structurally, CIC is different from other SWFs. CIC's capital flows

from foreign exchange reserves that sit under the State Affairs Foreign Exchange.

To finance CIC's creation, bonds were purchased from the Peoples Bank of China,

and therefore CIC is responsible for paying-out on these bonds annually. Thus,

CIC needs to pay interest costs and needs fast payouts. There was a need

for China to balance the upward pressure on its currency because of its forex

surplus. However, the sheer size of Chinese investments makes The West

uncomfortable and fears persist.

What has actually happened is that now CIC holds substantial stakes

in a number of Western companies and assets and with this comes clout. It’s

just the nature of things that China’s size would make many countries wary. It

is also a possibility that these fears could come true.

Investment Sectors

China’s key concerns are securing resources for its energy and

other resource needs. As China continues to grow, from an elevated base, many

of these supplies are becoming critical.

Portfolio Disclosure at Year-End 2018 showed an approximate

portfolio allocation of 38% public equities, 44% alternative assets, 15%

fixed-income securities and 2% cash. Of its public equity holdings, 54% were in

the U.S. and 33% in non-U.S. developed markets, while 13% were in emerging

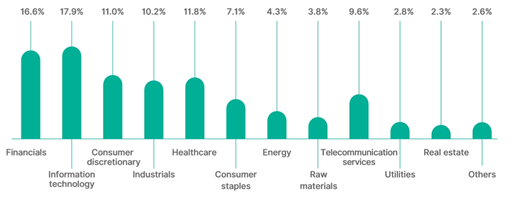

markets. The two biggest areas of CIC's equity investment were financials and

information technology. Nearly half of its fixed-income holdings were sovereign

bonds.

It may be noted here that AIFs (Hedge funds, Private Equity Funds,

etc) accounted for 44% of the investments and investments in publicly listed

companies only 38%. AIF included investments in energy and communications

infrastructure, agriculture, manufacturing, and health care. In a sense, it is

a very well-diversified basket that addresses the various objectives that the

fund has.

Global Investment Portfolio Distribution, as of 31 December 2019

(Source: CIC website)

Public Equity investments by sectors

Public Equity investments by region

It is a global investor with a vast portfolio, and is already a player in infrastructure, with projects like Heathrow Airport, serving London; Thames Water, which supplies to London; and the Port of Melbourne in Australia. Regulatory barriers have made such “symbolic investments” difficult in The USA, but other countries have been more welcoming. There are a number of ports in Europe, for example, where China has made strategic investments. It helps that trade with China is growing in Europe and many of these ports were struggling and in need of cash infusion. The expanding China-Europe trade itself provides a lifeline to these ports.

It is apparent that the needs and the objectives of China are very different from Norway. Further, in the case of China, it is only at the beginning of its journey and this fund would ultimately be multiple times the size of the Norwegian SWF within the next two decades. The sheer size and the economic might of China will surely lead to a big influence on the international financial markets. It is obviously something well beyond whatever the world has ever experienced. It’s not inconceivable to imagine the China SWF will be of the order of USD 3 trillion by 2030 itself, both as a consequence of growth and more capital infusion. Such large amounts will have an incredible impact on global financial markets.

Part 1 – What are Sovereign Wealth Funds

Part 2 - The story of the Norwegian SWF and The SWF of China

Part 3 – Singapore and a few more prominent SWFs

Part 4 – India as a prominent destination for SWFs

Comments

Post a Comment