The printing press, literacy, industrial revolution, human capital

German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg is credited with inventing the printing press around 1436, although he was far from the first to automate the book-printing process. Woodblock printing in China dates back to the 9th century and Korean bookmakers were printing with moveable metal type a century before Gutenberg.

But most historians believe Gutenberg’s adaptation, which employed a screw-type wine press to squeeze down evenly on the inked metal type, was the key to unlocking the modern age. With the newfound ability to inexpensively mass-produce books on every imaginable topic, revolutionary ideas and priceless ancient knowledge were placed in the hands of every literate European, whose numbers doubled every century.

How was printing done before the invention of the printing press?

Before the printing press became widespread across Europe, books were produced as manuscripts. These were hand-written books, mostly produced by scribes, monks and other church officials, and were valuable possessions, made of expensive materials, and individually commissioned by a lord or noble.

Gutenberg’s press and others of its era in Europe owed much to the medieval paper press, which was in turn modeled after the ancient wine-and-olive press of the Mediterranean area. A long handle was used to turn a heavy wooden screw, exerting downward pressure against the paper, which was laid over the type mounted on a wooden platen. Gutenberg used his press to print an edition of the Bible in 1455; this Bible is the first complete extant book in the West, and it is one of the earliest books printed from movable type. (Jikji, a book of the teachings of Buddhist priests, was printed by hand from movable type in Korea in 1377.) In its essentials, the wooden press used by Gutenberg reigned supreme for more than 300 years, with a hardly varying rate of 250 sheets per hour printed on one side.

Metal presses began to appear late in the 18th century, at about which time the advantages of the cylinder were first perceived and the application of steam power was considered. By the mid-19th century Richard M. Hoe of New York had perfected a power-driven cylinder press in which a large central cylinder carrying the type successively printed on the paper of four impression cylinders, producing 8,000 sheets an hour in 2,000 revolutions. The rotary press came to dominate the high-speed newspaper field, but the flatbed press, having a flat bed to hold the type and either a reciprocating platen or a cylinder to hold the paper, continued to be used for job printing.

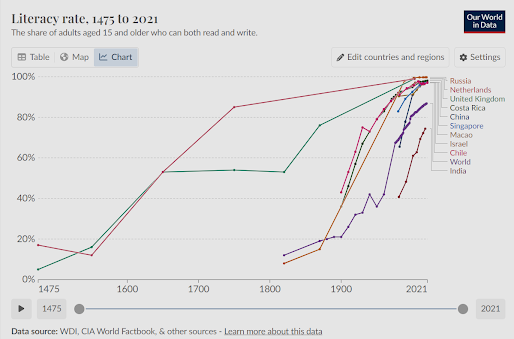

literacy rates rose from 11% in 1500 to 60% in 1750. from 1450 to 1550, literacy rates in Germany and Britain climbed from 7% to around 16%. Over the next century the number of literate adults doubled in Germany and tripled in Britain, and remained at this level until the early nineteenth century. From 1820 to the present day (after the industrial revolution), literacy rates incrementally increased to 99%, with the current world average being 83%.

Detailed data and graphics on the rise of literacy here -

https://ourworldindata.org/literacy

If only a minority of the population could read, how did they know of current events? How did they come into contact with new ideas?

For most, their primary means of hearing news came via word-of-mouth. Another important channel of information was cheap print. By printing pamphlets and ballads, messages could be disseminated through oral, aural and visual means.

"The wave of ideas that drove the Industrial Revolution didn’t fall out of the ether. Literacy in England had been steadily rising since the 16th century when between the 1720s and 1740s, it skyrocketed. In just two decades, literacy rose from 58 percent to 70 percent among men and from 26 percent to 32 percent among women. The three economists combed through historical documents searching for an explanation and discovered a startling rise in school establishments starting in 1700 and extending through 1740. In just 40 years, 988 schools were founded in Britain, nearly as many as had been established in previous centuries."

(source: https://persquaremile.com/2011/11/11/population-density-fostered-literacy-the-industrial-revolution/ )

The level of human capital in England was amongst the highest in Europe before the Industrial Revolution. Between 1500 and 1800 male literacy rates had increased from 10 % to 60 % (Cressy [1980]) and the level of book consumption per capita had increased more than ten times (Baten and van Zanden [2008]). Similar conclusions can be drawn from numeracy rates, another important component of human capital as it is argued to measure more cognitive reasoning abilities (A’Hearn et al. [2009]).

.....

A Tale of Two “Educational Revolutions”. Human Capital Formation in England in the Long Run

Alexandra M. de Pleijt

https://www.cairn.info/revue-d-economie-politique-2020-1-page-107.htm

Comments

Post a Comment