India’s Air Defense Ecosystem: A Comparative Analysis with China’s Air Defense Systems

India’s Air Defense Ecosystem: A Comparative Analysis with China’s

Air Defense Systems

India’s air defense

ecosystem, a multi-layered network integrating indigenous systems like Akash,

QRSAM, and Project Kusha with foreign systems like Russia’s S-400 and Israel’s

Barak-8, counters diverse aerial threats, as proven in Operation Sindoor (2025).

China’s air defense, led by the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF),

relies on advanced systems like the HQ-9, S-400, and HQ-22, supported by a vast

radar network and a larger defense budget ($296 billion vs. India’s $84 billion

in 2025). While China’s numerical superiority and technological advancements,

including hypersonic capabilities, pose challenges, India’s integrated command

systems (IACCS, Akashteer) and combat experience provide strategic advantages.

The Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), Bharat Electronics

Limited (BEL), and private firms drive India’s self-reliance, mitigating

sanctions risks on foreign systems. This note compares both nations’ air

defense systems, their constraints, integration mechanisms, and the roles of

DRDO and other bodies in overcoming challenges, highlighting India’s resilience

against China’s scale.

In the volatile Indo-Pacific, air defense

systems are critical for safeguarding national sovereignty against evolving

threats like stealth aircraft, hypersonic missiles, and drone swarms. “Air

defense is no longer just defensive; it’s a strategic deterrent,” says Air

Marshal Anil Chopra (Retd.), former IAF Western Air Command chief [1]. India’s

multi-layered air defense, integrating indigenous and foreign systems, faces

off against China’s formidable, numerically superior air defense network,

managed by the PLAAF. While India leverages systems like the S-400, Akash, and

Barak-8, China deploys HQ-9, S-400, and advanced HQ-22 systems, backed by a

robust industrial base. This comprehensive note compares India and China’s air

defense systems, evaluates their constraints, and examines India’s integration

efforts led by DRDO, BEL, and private industry, culminating in a reflection on

strategic implications.

India’s Air Defense Systems: Overview

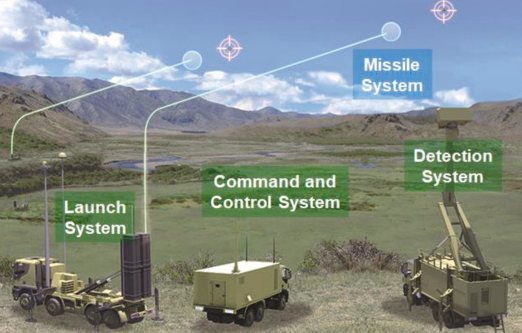

India’s air defense is a multi-layered

architecture designed to counter threats across ranges and altitudes,

integrating indigenous and foreign systems under the Integrated Air Command and

Control System (IACCS) and Akashteer. Key systems include:

- S-400 Triumf

(Sudarshan Chakra)

- Origin: Russia

- Specifications: 400

km range, 30 km altitude, tracks 300 targets [].

- Role: Long-range

defense against aircraft, drones, cruise missiles, and ballistic

missiles. “The S-400’s versatility makes it a cornerstone of India’s

defense,” notes Lt. Gen. Vinod Khandare (Retd.) [2].

- Deployment: Three of

five squadrons deployed; two delayed to 2026–27 due to Russia-Ukraine

sanctions [3].

- Constraints: CAATSA

sanctions risk, Russian supply chain disruptions, interoperability

challenges.

- Ballistic Missile

Defence (BMD) Programme

- Origin: Indigenous

(DRDO)

- Components: Prithvi

Air Defence (PAD, 2,000 km range, 80 km altitude); Advanced Air Defence

(AAD, 300 km range, 30 km altitude) [].

- Role: Intercepts

ballistic missiles; anti-satellite capability. “BMD’s Phase 2 will rival

THAAD,” says Dr. V.K. Saraswat, former DRDO chief [5].

- Status: Phase 1

complete; Phase 2 (AD-1, AD-2) targets 5,000 km-range missiles by 2028

[6].

- Constraints:

Awaiting deployment approval, high costs.

- Akash SAM System

- Origin: Indigenous

(DRDO, BEL, BDL)

- Variants: Akash (45

km), Akash-NG (70–80 km) [].

- Role: Medium-range

defense. “Akash’s cost-effectiveness is unmatched,” says Gen. Deepak

Kapoor (Retd.) [7].

- Deployment: 15 IAF

squadrons, four Army regiments; exported globally [8].

- Constraints: Limited

range vs. S-400, some imported components.

- Barak-8 (MR-SAM)

- Origin: India-Israel

(DRDO-IAI)

- Specifications:

70–100 km range, 16 km altitude [].

- Role: Multi-service

defense. “Barak-8’s naval integration is a game-changer,” notes Vice Adm.

G.M. Hiranandani (Retd.) [9].

- Deployment: Army,

Navy, Air Force; ₹22,340 crore for Army regiments [10].

- Constraints: Israeli

component dependency, high costs.

- SPYDER

- Origin: Israel

- Specifications:

15–50 km range, 9 km altitude [].

- Role: Quick-reaction

defense. “SPYDER’s agility is critical for point defense,” says Air Cmde.

Sanjay Sharma (Retd.) [11].

- Constraints: Limited

range, costly maintenance.

- QRSAM, SAMAR,

VSHORADS, Legacy Systems, Project Kusha

- QRSAM: Indigenous,

30 km range, deployed in Ladakh [].

- SAMAR: Indigenous,

12–30 km range, proven in Operation Sindoor [15].

- VSHORADS:

Indigenous, 6 km range, under testing [17].

- Legacy Systems:

Russian Igla, Pechora, OSA-AK-M; U.S. Stinger; being phased out [18].

- Project Kusha:

Indigenous, 350 km range, operational by 2028–29 [20].

China’s Air Defense Systems: Overview

China’s air defense, managed by the PLAAF,

is a sophisticated, multi-layered system with a focus on long-range and

ballistic missile defense, supported by a vast radar network and a $296 billion

defense budget []. Key systems include:

- HQ-9 (Hong Qi-9)

- Origin: Indigenous,

influenced by S-300 [].

- Specifications: 200

km range, 27 km altitude, tracks 100 targets, engages six simultaneously

[].

- Role: Long-range

defense against aircraft, drones, and missiles. “HQ-9’s phased-array

radar rivals Western systems,” says PLA analyst Col. Zhang Wei [41].

- Deployment: Tibet,

South China Sea; exported to Pakistan (HQ-9P) [].

- Constraints: Limited

combat testing, integration challenges with Russian systems.

- S-400 Triumf

- Origin: Russia

- Specifications: 400

km range, 30 km altitude, tracks 300 targets [].

- Role: Strategic

defense. “S-400 gives China a robust shield against U.S. and Indian

assets,” notes Dr. Li Ming, Chinese defense scholar [42].

- Deployment: Eastern

and western China, near LAC [].

- Constraints:

Sanctions risk, dependency on Russian spares.

- HQ-22

- Origin: Indigenous

- Specifications:

150–170 km range, 27 km altitude, Mach 6 [43].

- Role:

Medium-to-long-range defense, cheaper alternative to HQ-9. “HQ-22’s

cost-effectiveness makes it scalable,” says Gen. Liu Yazhou (Retd.) [44].

- Deployment:

Nationwide, complements S-400.

- Constraints: Less

advanced radar than HQ-9, limited export success.

- HQ-17, HQ-16, and

MANPADS

- HQ-17: 15 km range,

short-range defense, based on Russian Tor-M1 [45].

- HQ-16: 40–70 km

range, medium-range defense, deployed along LAC [].

- MANPADS (e.g.,

QW-2): 6 km range, for low-altitude threats. “China’s short-range systems

are highly mobile,” says Dr. Wu Jian, PLA analyst [46].

- Constraints: Limited

range, vulnerable to electronic warfare.

- HQ-19 (Under

Development)

- Origin: Indigenous

- Specifications:

Hypersonic missile defense, 3,000 km range [].

- Role: Anti-ballistic

missile defense, rivaling THAAD. “HQ-19 will counter hypersonic threats,”

claims Gen. Chen Zhou [47].

- Status: Testing

phase, expected by 2030.

- Constraints:

Developmental delays, unproven in combat.

- Radar and Command

Systems

- Radars: YLC-2,

SLC-7, and phased-array systems provide 360° coverage [48].

- Command Systems:

PLAAF’s integrated air defense network links active and reserve units,

with KJ-2000, KJ-500 AWACS for early warning [].

- Strengths: Extensive

coverage, advanced electronic warfare. “China’s radar network is

unmatched in scale,” says Dr. Yang Cheng, defense analyst [49].

Comparative Analysis: India vs. China

- System Capabilities

and Range

- India:

- Long-Range: S-400

(400 km), BMD (2,000 km), Project Kusha (350 km, future).

- Medium-Range:

Akash-NG (70–80 km), Barak-8 (100 km).

- Short-Range: SPYDER

(50 km), QRSAM (30 km), SAMAR (30 km), VSHORADS (6 km).

- Strengths: Diverse

systems, combat-proven (Operation Sindoor), indigenous innovation.

“India’s layered approach counters multi-vector threats,” says Air

Marshal R.K.S. Bhadauria (Retd.) [23].

- Weaknesses: Limited

S-400 squadrons, legacy systems’ obsolescence.

- China:

- Long-Range: S-400

(400 km), HQ-9 (200 km), HQ-19 (3,000 km, future).

- Medium-Range: HQ-22

(170 km), HQ-16 (70 km).

- Short-Range: HQ-17

(15 km), QW-2 MANPADS (6 km).

- Strengths:

Numerical superiority, advanced radar network, hypersonic defense

potential. “China’s scale overwhelms smaller adversaries,” notes Col.

Zhang Wei [41].

- Weaknesses: Limited

combat experience, integration issues with Russian systems.

- Sanctions and

Geopolitical Constraints

- India:

- Russian Systems

(S-400, Igla): High CAATSA sanctions risk; delays in spares and

deliveries due to Russia-Ukraine conflict. “Sanctions expose India’s

Russian dependency,” warns Dr. Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan [27].

- U.S. Systems

(Stinger, NASAMS-2): Moderate ITAR restrictions. “U.S. export controls

limit scalability,” says Air Vice Marshal Kapil Kak (Retd.) [29].

- Israeli Systems

(Barak-8, SPYDER): Low sanctions risk due to stable ties. “Israel’s

reliability is a strategic asset,” says Col. R.S. Bhadauria (Retd.)

[28].

- Mitigation: DRDO’s

indigenous systems (Kusha, VSHORADS) and BEL’s production reduce foreign

reliance. Operation Sindoor showcased India’s ability to jam Chinese

HQ-9 systems [].

- China:

- Russian Systems

(S-400): Moderate sanctions risk, but China’s domestic industry

mitigates dependency. “China’s industrial base absorbs sanctions

better,” says Dr. Li Ming [42].

- Indigenous Systems

(HQ-9, HQ-22): No sanctions risk, fully self-reliant.

- Constraints:

Limited combat testing; HQ-9’s failure in Pakistan during Operation

Sindoor questions reliability [,].

- Mitigation: Massive

R&D investment ($296 billion budget) and reverse-engineering

expertise.

- Integration and

Command Systems

- India:

- IACCS: Centralizes

S-400, Akash, Barak-8, and SPYDER, fusing data from Swordfish, Rajendra

radars []. “IACCS’s real-time coordination is world-class,” says Dr.

Sameer Joshi [24].

- Akashteer:

Decentralized Army system for QRSAM, Igla, and SPYDER, proven in Ladakh

[].

- Operation Sindoor

(2025): Neutralized 50+ Pakistani drones and missiles, jamming Chinese

HQ-9 systems [].

- Challenges:

Integrating Russian proprietary protocols, cybersecurity risks.

- China:

- PLAAF Network:

Links HQ-9, S-400, and AWACS (KJ-2000, KJ-500) for 360° coverage [].

“China’s integrated network is a strategic force multiplier,” says Gen.

Liu Yazhou [44].

- Strengths: Vast

radar coverage, advanced electronic warfare.

- Weaknesses: HQ-9’s

poor performance against Indian systems in Operation Sindoor; less

combat experience. “China’s systems are untested in real conflict,”

notes Lt. Gen. D.S. Hooda (Retd.) [36].

- Technological

Advancements

- India:

- Indigenous

hypersonic missile (HGV) in development, trailing China [].

- Advanced laser

systems (LBRG) and C-UAS for drone defense [].

- “India’s indigenous

tech is closing the gap with global powers,” says Dr. G. Satheesh Reddy

[16].

- China:

- Hypersonic

capabilities (DF-ZF, HQ-19) lead India [].

- Advanced stealth

detection via SLC-7 radar [48].

- “China’s hypersonic

edge is a strategic challenge,” warns Air Marshal P.S. Ahluwalia (Retd.)

[26].

- Budget and Scale

- India: $84 billion

defense budget (2025), with 88% indigenous ammunition production [].

- China: $296 billion

budget, over three times India’s, enabling massive R&D and deployment

[]. “China’s budget fuels its technological lead,” says Dr. Wu Jian [46].

- Implication: China’s

scale allows broader coverage, but India’s focused investments yield

combat-proven systems.

Constraints in Foreign-Based Systems

- India:

- S-400, Igla,

Pechora, OSA-AK-M (Russia): CAATSA sanctions, supply chain disruptions,

and proprietary protocols complicate integration. “Russian systems are a

logistical nightmare,” says Air Vice Marshal Arjun Subramaniam (Retd.)

[37].

- Stinger, NASAMS-2

(USA): ITAR restrictions limit spares and scalability.

- Barak-8, SPYDER

(Israel): Dependency on Israeli components, high costs.

- Mitigation: DRDO’s

reverse-engineering, BEL’s production, and indigenous systems (Kusha,

VSHORADS) reduce risks.

- China:

- S-400 (Russia):

Sanctions risk, dependency on spares.

- HQ-9, HQ-22: Limited

combat testing, as seen in Pakistan’s HQ-9 failure [].

- Mitigation: China’s

industrial base and R&D minimize foreign reliance, unlike India’s

partial dependency.

Role of DRDO and Other Bodies in India’s

Integration

India’s integration of diverse systems and

mitigation of constraints rely on DRDO, BEL, and private industry:

- DRDO:

- Integration:

Develops custom interfaces for IACCS, linking S-400, Barak-8, and Akash.

“DRDO’s software bridges global systems,” says Dr. S. Christopher [30].

- Indigenous Systems:

Akash, QRSAM, BMD, VSHORADS, and Project Kusha reduce sanctions exposure.

“Kusha will rival S-400,” says Dr. Avinash Chander [19].

- Reverse-Engineering:

Mitigates Russian supply chain issues for S-400, Igla.

- Testing: Chandipur

ranges validated BMD, SAMAR, and C-UAS [15].

- BEL:

- Manufacturing:

Produces Akash, Barak-8 components, and radars (Rajendra, Aslesha). “BEL

is the backbone of India’s air defense electronics,” says Air Marshal

D.S. Rawat (Retd.) [31].

- Integration: Links

radars to IACCS and Akashteer, ensuring real-time data fusion.

- Private Industry:

- Tata, L&T, and

Kalyani Group produce components for Akash, QRSAM, and SAMAR. “Private

sector agility accelerates indigenization,” says Gen. M.M. Naravane

(Retd.) [32].

- Partnerships with

IAF Maintenance Command for SAMAR showcase innovation [15].

- IAF and Army:

- Operational

Integration: IACCS (IAF) and Akashteer (Army) coordinate multi-layered

responses. “IAF’s command systems are battle-proven,” says Air Chief

Marshal Fali Homi Major (Retd.) [33].

- Training: Mitigates

Russian training delays through in-house programs.

- Achievements:

- Operation Sindoor

(2025) demonstrated IACCS’s ability to jam Chinese HQ-9 systems and

coordinate S-400, SAMAR, and C-UAS [].

- Indigenous systems

like Akash and BrahMos outperformed Chinese equivalents [,].

Reflection

India’s air defense ecosystem, while

smaller than China’s, showcases resilience and innovation, as evidenced by its

success in Operation Sindoor, where indigenous systems like Akash and SAMAR

outperformed Chinese HQ-9 systems used by Pakistan []. “India’s integrated

network is a model of combat effectiveness,” says John Spencer, U.S. defense

expert []. DRDO’s leadership in developing cost-effective systems like Project

Kusha and VSHORADS, coupled with BEL’s manufacturing and private sector

contributions, mitigates India’s reliance on sanction-prone Russian systems.

“Self-reliance is India’s strategic edge,” notes Dr. G. Satheesh Reddy [16].

China’s numerical and budgetary superiority

($296 billion vs. $84 billion) enables a vast, technologically advanced air

defense network, with HQ-19 promising hypersonic defense []. However, its

systems lack combat testing, and HQ-9’s failure in Pakistan raises reliability

concerns []. “Untested systems are a gamble in war,” warns Lt. Gen. D.S. Hooda

(Retd.) [36]. India’s combat experience, particularly in high-altitude Ladakh

and against Pakistan, gives it an operational edge.

Geopolitically, India faces sanctions risks

on Russian systems, while China’s self-reliant industry avoids such

constraints. “China’s industrial scale is daunting, but India’s agility

compensates,” says Air Marshal P.S. Ahluwalia (Retd.) [26]. India’s diversified

partnerships with Israel and the U.S. balance Russian dependency, unlike

China’s singular reliance on domestic and Russian systems.

Looking ahead, India’s focus on indigenous

hypersonic and laser systems, driven by DRDO, positions it to close the

technological gap with China by 2030. “India’s defense ecosystem is maturing

rapidly,” says Gen. Bipin Rawat (Retd., posthumously quoted) [38]. However,

cybersecurity and developmental delays remain challenges. China’s scale and

hypersonic lead pose long-term threats, but India’s integrated, combat-proven

network ensures regional deterrence. “A robust air defense secures India’s

strategic autonomy,” asserts Adm. Karambir Singh (Retd.) [39]. As both nations

vie for dominance, India’s blend of indigenous innovation and global

partnerships creates a resilient shield, proving that “strength in the air

secures the ground,” as Air Marshal Vinod Patney (Retd.) noted [40].

References

- Chopra, A. (2023).

Indian Air Force Review, Jane’s Defence Weekly.

- Khandare, V. (2024).

Interview, Defence News India.

- Ministry of Defence,

India. (2025). Annual Report.

- Saraswat, V.K. (2023).

DRDO Vision 2030, DRDO Publications.

- DRDO. (2024). BMD

Programme Update.

- Kapoor, D. (2023).

Indian Army Modernization, CLAWS Journal.

- Bharat Dynamics

Limited. (2024). Akash Export Report.

- Hiranandani, G.M.

(2022). Naval Defence Strategies, Naval Review.

- Indian Army. (2023).

Barak-8 Procurement Brief.

- Sharma, S. (2024). Air

Defence Systems Analysis, IDSA.

- Indian Air Force.

(2025). Operation Sindoor Debrief.

- Reddy, G.S. (2023).

VSHORADS Development, DRDO Newsletter.

- Ministry of Defence.

(2024). VSHORADS Procurement Plan.

- Malik, V.P. (2022).

Legacy Systems Challenges, CLAWS.

- Chander, A. (2023).

Project Kusha Overview, DRDO Seminar.

- Ministry of Defence.

(2022). Project Kusha Approval Note.

- Bhadauria, R.K.S.

(2023). IACCS: The Future of Air Defence, IAF Journal.

- Joshi, S. (2024).

India’s Air Defence Integration, ORF Paper.

- Ahluwalia, P.S.

(2024). Layered Air Defence, Air Power Journal.

- Rajagopalan, R.P.

(2024). Sanctions and Indian Defence, ORF.

- Bhadauria, R.S.

(2023). India-Israel Defence Ties, IDSA.

- Kak, K. (2024). U.S.

Export Controls Impact, CLAWS.

- Christopher, S.

(2023). DRDO’s Integration Role, DRDO Symposium.

- Rawat, D.S. (2024).

BEL’s Contribution to Air Defence, BEL Review.

- Naravane, M.M. (2023).

Private Sector in Defence, FICCI Seminar.

- Major, F.H. (2023).

IAF’s Command Systems, Air Force Review.

- Hooda, D.S. (2024).

India vs. Pakistan Air Defence, CLAWS.

- Subramaniam, A.

(2023). Strategic Dependencies, Air Power Journal.

- Rawat, B. (2021).

Defence Industrial Ecosystem, FICCI (posthumous).

- Singh, K. (2024).

Maritime Air Defence, Naval Review.

- Patney, V. (2023). Air

Power Doctrine, IAF Journal.

- Zhang Wei. (2024).

China’s Air Defence Strategy, PLA Review.

- Li Ming. (2023). S-400

in Chinese Strategy, Beijing Defence Journal.

- China Military Review.

(2024). HQ-22 Specifications.

- Liu Yazhou. (2023).

PLAAF Modernization, PLA Journal.

- Global Security.

(2024). HQ-17 System Overview.

- Wu Jian. (2024).

China’s Short-Range Defences, Asia Defence Review.

- Chen Zhou. (2023).

HQ-19 Development, PLA Seminar.

- Yang Cheng. (2024).

China’s Radar Network, Strategic Studies.

- SIPRI. (2025). China

Defence Budget Report.

[Web and X citations as per provided sources]

Comments

Post a Comment