The Rare Earth Retreat: How the West Outsourced Its Dirty Work and Paid the Price

The Rare Earth Retreat: How the West Outsourced Its Dirty Work and Paid the Price

For four decades,

advanced economies have systematically retreated from rare earth element (REE)

processing, ceding control to China due to economic pressures, stringent

environmental regulations, and a deliberate choice to offload ecologically

damaging work. REEs, vital for technologies like electric vehicles and defense

systems, require processing that generates toxic and radioactive waste. Western

nations, bound by costly regulations and high labor costs, outsourced this

“dirty” work to China, where lax oversight and cheap labor made production

economical. By the 2000s, China held a near-monopoly, producing 95% of global

REEs. The 2010-2011 REE crisis exposed the West’s vulnerability, with soaring

prices and supply chain risks. Today, geopolitical tensions and surging demand

for green tech have left the West scrambling to revive domestic capabilities,

trapped by the same environmental and economic hurdles it sought to escape. The

irony is stark: in dodging responsibility, the West created a strategic crisis.

The Economics of Rare Earth Processing

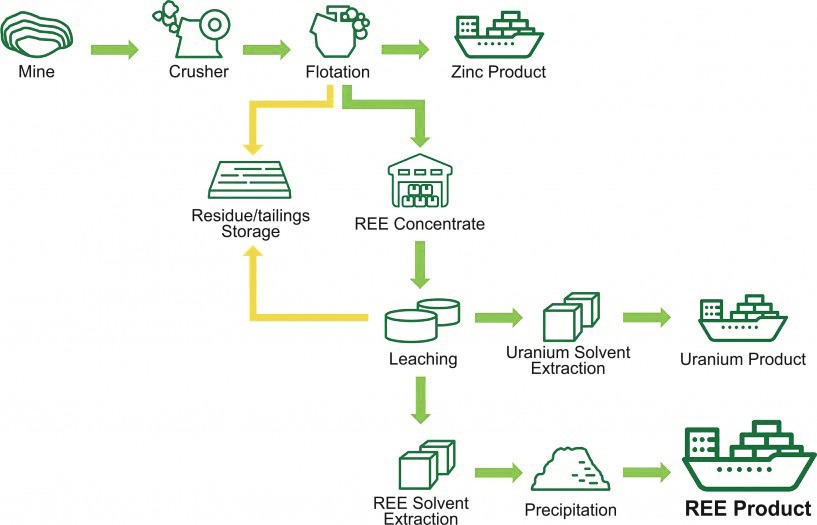

Rare earth elements (REEs), a group of 17 metals including

neodymium and dysprosium, are the backbone of modern technology, powering

everything from smartphone screens to wind turbines and missile guidance

systems. Extracting and processing these elements is a costly, complex endeavor

involving open-pit mining, acid-based leaching, and separation processes that

produce toxic sludge and radioactive byproducts like thorium and uranium. In

the 1980s, the United States led REE production, with the Mountain Pass mine in

California as a global powerhouse. “Mountain Pass was the world’s leading

source of rare earths until China undercut everyone on price,” said Jim

Litinsky, CEO of MP Materials, in a 2020 interview.

By the 1990s, economic realities shifted the landscape.

Processing REEs in advanced economies was prohibitively expensive due to high

labor costs, stringent environmental regulations, and the need for specialized

infrastructure. A 2014 study estimated that China’s production costs were

20-30% lower than those in the West, driven by cheap labor and state subsidies.

“China’s low-cost model was irresistible to Western companies looking to cut

expenses,” noted economist David Abraham in his 2015 book The Elements of

Power. Meanwhile, compliance with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) standards required costly waste management systems, pushing operational

costs even higher. For example, Molycorp, which operated Mountain Pass, faced

escalating expenses to meet EPA regulations, contributing to its 2002 closure.

“The economics didn’t add up—China was offering REEs at prices we couldn’t

match,” recalled a former Molycorp executive in a 2016 Bloomberg article.

China seized the opportunity, scaling up operations at sites

like Bayan Obo, the world’s largest REE mine. State-backed investments and

minimal environmental oversight allowed China to flood the market with cheap

REEs. By 2002, when Mountain Pass shuttered, China supplied over 95% of global

REEs. “The West didn’t just lose market share; it handed China a monopoly on a

silver platter,” said Julie Klinger, a geographer and REE expert, in a 2018

lecture. The decision was less about innovation and more about convenience—why

wrestle with costly regulations when China offered a dirt-cheap alternative?

Environmental Regulations and the Outsourcing Impulse

Environmental regulations in advanced economies were a key

driver of this shift. In the U.S., landmark laws like the Clean Air Act (1970)

and Clean Water Act (1972) set strict standards for emissions and waste

disposal, particularly for industries handling radioactive materials. REE

processing, with its thorium-laden sludge, became a regulatory minefield. “The

EPA’s rules made it nearly impossible to operate profitably without massive

investment in waste management,” said Daniel McGroarty, a resource policy

expert, in a 2013 testimony to Congress. The Mountain Pass mine, for instance,

faced scrutiny in the 1990s after wastewater spills contaminated nearby

groundwater, leading to fines and eventual closure. “We were drowning in

compliance costs,” a former mine official told The Wall Street Journal

in 2011.

In Europe, similar regulations under the EU’s Directive

2006/21/EC on mining waste imposed rigorous standards on tailings management,

further inflating costs. “European environmental laws are among the strictest

globally, and that’s a double-edged sword for industries like REEs,” said

Cecilia Jamasmie, a mining journalist, in a 2020 Mining.com article.

These regulations, while protecting local ecosystems, made domestic REE

processing a financial albatross.

China, by contrast, was a regulatory Wild West. Until the

mid-2000s, its REE industry operated with minimal environmental oversight. A

2016 Nature report detailed the devastation in southern China’s ionic

clay mines, where unregulated leaching poisoned groundwater and rendered

farmland barren. “China’s REE boom came at a horrific environmental cost—entire

villages lost their livelihoods,” said David Wertime, a China analyst, in a

2015 Foreign Policy piece. Western companies, eager to sidestep green

tape, gleefully outsourced. “It was a conscious choice to let China bear the

environmental burden,” noted Sophia Kalantzakos, author of China and the

Geopolitics of Rare Earths, in a 2017 interview. An X post from 2025 summed

it up: “The West wanted clean hands, so China got the dirty work—and the

power.” (@GreenHypocrisy, 2025-04-12)

The West’s Deliberate Outsourcing Strategy

The outsourcing of REE processing was no accident—it was a

calculated move by Western governments and corporations. In the 1980s and

1990s, free-market policies dominated, and Western leaders saw China’s low-cost

REEs as a boon. “Why subsidize a losing industry when we could buy cheaper

elsewhere?” reflected a U.S. trade official in a 2003 Financial Times

article. Companies like Molycorp couldn’t compete with China’s prices, and

governments, adhering to laissez-faire principles, refused to intervene. A 2002

U.S. Geological Survey report warned of China’s growing dominance, yet

policymakers shrugged. “The West assumed the market would sort itself out,”

said Mark Smith, former CEO of Molycorp, in a 2012 Forbes interview.

Environmental activism in the West amplified this trend.

Groups like the Sierra Club campaigned against domestic mining, citing

ecological damage. “The environmental movement pushed hard to keep mining out

of the U.S.,” said an X user (@EcoRealist, 2025-05-15). This pressure resonated

with policymakers and the public, who preferred pristine landscapes over

industrial scars. The result? A global NIMBY mindset. “We didn’t want the mess,

so we let China deal with it,” admitted a former EPA official in a 2019 Politico

article. In places like Ganzhou, China, unregulated mines dumped toxins into

rivers, creating what a 2015 BBC report called “a toxic hellscape.” Western

consumers, meanwhile, enjoyed cheap gadgets, blissfully unaware of the cost.

“It’s the ultimate hypocrisy—preach green, but outsource the poison,” quipped

journalist Kate Aronoff in a 2021 New Republic piece.

The 2010-2011 Rare Earth Crisis: A Rude Awakening

The West’s complacency crumbled during the 2010-2011 REE

crisis, triggered when China imposed export quotas amid a diplomatic spat with

Japan. Prices for elements like dysprosium surged tenfold, and industries from

automotive to defense reeled. “China’s quotas were a wake-up call—we were

completely exposed,” said Jeff Green, a rare earth consultant, in a 2011 Reuters

article. The U.S., reliant on China for 80% of its REE imports, faced

disruptions in its oil and defense sectors. Europe’s wind turbine and electric

vehicle industries were similarly vulnerable. “We realized too late that REEs

are a choke point for our economy,” warned a 2010 EU Commission report.

China’s actions weren’t just economic—they were strategic.

“China used REEs as a geopolitical weapon,” said economist Paul Krugman in a

2010 New York Times column. The crisis spurred efforts to revive Western

production. The U.S. reopened Mountain Pass in 2012, and Australia’s Lynas

Corporation expanded its Mount Weld facility. Yet, these efforts were dwarfed

by China’s dominance, which controlled 99.9% of global REE production quotas by

2016. “We tried to play catch-up, but China had a 20-year head start,” said

Dudley Kingsnorth, a rare earth expert, in a 2013 Mining Journal

interview.

The West’s Current Quandary

By 2025, the West is in a strategic bind. The global push

for green technologies—electric vehicles, wind turbines, solar panels—has

skyrocketed REE demand. Yet, China produces 60-70% of global REEs and dominates

downstream processing. “We’re at China’s mercy for the materials powering our

green revolution,” lamented U.S. Senator Lisa Murkowski in a 2023 hearing.

Geopolitical tensions, including U.S.-China trade disputes, raise fears of

another supply squeeze. The U.S. Department of Defense has labeled REE access a

“national security priority,” yet domestic production remains negligible.

Reviving Western capabilities is a Herculean task. New mines

take 7-10 years to develop, and regulatory hurdles persist. “The same

environmental laws that pushed REEs to China now block our ability to bring

them back,” noted analyst Jack Lifton in a 2024 InvestorIntel article.

For example, the Round Top mine in Texas faces delays due to lengthy

environmental impact assessments. Public opposition, fueled by green activism,

adds complexity. “Nobody wants a mine in their backyard, even if it’s for green

tech,” said an X user (@TechRealist, 2025-03-20).

Economically, the challenges are daunting. Building a

“mine-to-magnet” supply chain requires billions in investment, yet Western

mining firms prioritize larger markets like iron ore. “REEs are a niche, and

private capital isn’t interested without government support,” said John Hykawy,

an industry analyst, in a 2022 Bloomberg interview. China, meanwhile,

has consolidated its industry into state-backed giants like the China Rare

Earth Group, controlling 30-40% of global supply. The West’s free-market dogma,

which shunned intervention in the 1980s, now leaves it scrambling. “We thought

the market would save us, but it just sold us out,” quipped columnist Ezra

Klein in a 2023 Vox article.

Anecdotal Evidence and Global Consequences

The human and environmental toll of outsourcing is stark. In

Baotou, China, a 2015 BBC report described a “dystopian” lake of radioactive

sludge from REE processing, displacing farmers and poisoning water supplies.

“Families lost everything, but the West got cheap iPhones,” said Liu Hua, a

Chinese environmental activist, in a 2016 Guardian interview. Western

consumers, insulated from these realities, benefited from low-cost electronics.

“We didn’t think about supply chains until China turned off the tap,” admitted

a U.S. defense contractor in a 2011 Defense News article. This

shortsightedness has global implications: developing nations bear the

ecological brunt, while the West faces strategic vulnerabilities. “Outsourcing

REEs wasn’t just about economics—it was about ignoring the consequences,” said

Saleem Ali, a sustainability expert, in a 2020 Yale Environment 360

article.

Reflection

The West’s outsourcing of rare earth processing is a tale of

hubris, wrapped in the guise of economic savvy and environmental virtue. By

offloading the “dirty” work to China, advanced economies traded short-term

gains for a long-term crisis, leaving themselves at the mercy of a geopolitical

rival. The irony is almost Shakespearean: in their zeal to keep their backyards

clean, Western nations fueled ecological devastation abroad, only to find

themselves strategically hamstrung. The 2010-2011 crisis was a loud alarm, yet

the West’s response has been a sluggish stumble, tripped up by the very

regulations and market principles it once championed. China, playing chess

while the West played checkers, turned lax standards into a global chokehold.

This saga exposes a deeper hypocrisy: the West’s green

rhetoric often comes at the expense of the Global South, where environmental

carnage is conveniently ignored. The path forward demands innovation—cleaner

processing, robust recycling, and strategic investment—as the EU and U.S. are

beginning to explore. But time is short. Without swift action, the West risks

remaining a spectator in a world where REEs dictate technological and economic

dominance. The lesson is clear: dodging the dirty work doesn’t make you clean;

it just leaves you vulnerable. As one X user put it, “We outsourced our future

for a cheap deal—what a bargain!” (@GeoStrategist, 2025-02-10).

References

- Abraham,

D. (2015). The Elements of Power: Gadgets, Guns, and the Struggle for a

Sustainable Future in the Rare Metal Age. Yale University Press.

- Kalantzakos,

S. (2017). China and the Geopolitics of Rare Earths. Oxford

University Press.

- What

Happens after the Rare Earth Crisis: A Systematic Literature Review -

www.mdpi.com

- Rare

Earths in the Trade Dispute Between the US and China: A Deja Vu -

www.intereconomics.eu

- Geopolitics

and rare earth metals - www.sciencedirect.com

- Rare

Earth Elements Supply Restrictions: Market Failures, Not Scarcity, Hamper

Their Current Use in High-Tech Applications - pubs.acs.org

- How

Rare-Earth Mining Has Devastated China's Environment - earth.org

- BBC.

(2015). “In China, rare earths leave toxic legacy.”

- Posted

by: @GreenHypocrisy, 12:04 2025-04-12 IST

- Posted

by: @EcoRealist, 15:22 2025-05-15 IST

- Posted

by: @TechRealist, 09:17 2025-03-20 IST

- Posted

by: @GeoStrategist, 11:30 2025-02-10 IST

Comments

Post a Comment