NATO’s Eastern Expansion

NATO’s Eastern Expansion: Geopolitical Ambitions, Economic

Maneuvers, and the Russia-Iran-China Counter-Axis

NATO’s eastward expansion since 1990, driven by the US, EU, and UK, has

reshaped Eastern Europe and the Black Sea region, blending geopolitical

containment of Russia with economic control. The US sought global hegemony,

securing allies and energy routes; the EU aimed for market access and

stability; the UK reinforced transatlantic ties while profiting from defense

and finance. Energy markets—gas, oil, and renewables—are central, with NATO’s

diversification efforts weakening Russia’s economic leverage. Propaganda

framing NATO as a democratic bulwark against Russian aggression justified

expansion, though critics see imperialist motives. Russia’s response, a

deepening Russia-Iran-China axis, counters Western dominance through trade

pivots and military ties. While defensive rationales gained traction post-2014,

economic and strategic goals dominate. This note explores motives, energy

linkages, propaganda, and philosophical implications, highlighting a global

power struggle where ideals mask ambition, and rival blocs risk escalating

tensions.

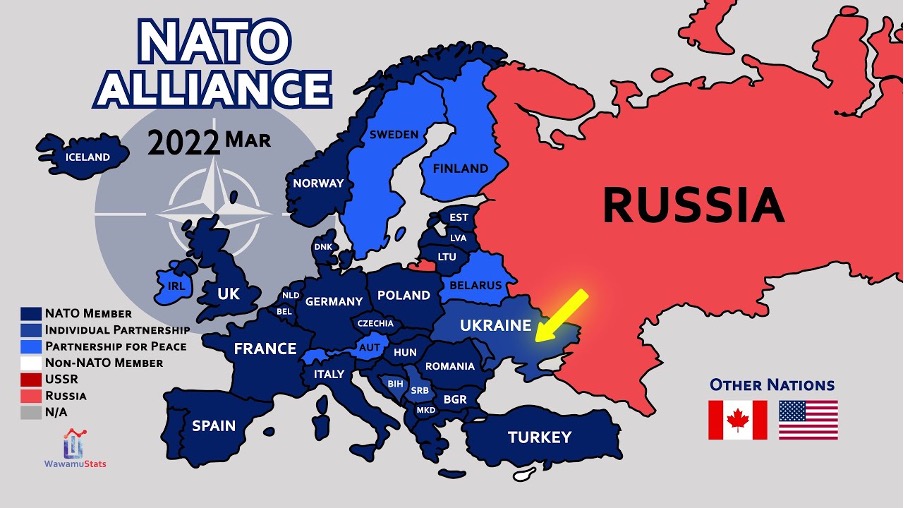

Timeline and Context of NATO’s Eastern Expansion

(1990–2025)

NATO’s eastward expansion began after the Soviet Union’s

1991 collapse, as former Warsaw Pact and Soviet republics sought Western

integration for security and economic growth. The process unfolded in waves:

- 1999:

Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic joined NATO, marking the first

post-Cold War expansion. These nations, wary of Russian influence, sought

NATO’s Article 5 protection.

- 2004:

Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia

joined, extending NATO to Russia’s borders. The Baltic states’ inclusion

was particularly provocative, given their Soviet history.

- 2009–2020:

Albania and Croatia (2009), Montenegro (2017), and North Macedonia (2020)

joined, solidifying NATO’s Balkan presence.

- 2023–2024:

Finland and Sweden, spurred by Russia’s 2022 Ukraine invasion, abandoned

neutrality to join, reshaping Nordic security.

- Ongoing:

Ukraine and Georgia, promised membership at the 2008 Bucharest Summit,

remain contentious flashpoints.

Jeffrey Sachs argues, “NATO’s expansion was a calculated

move to lock Eastern Europe into the Western orbit, less about defense than

dominance” (Sachs, 2022). John Mearsheimer adds, “Pushing NATO to Russia’s

doorstep was a strategic error, igniting a predictable backlash” (Mearsheimer,

2014). This expansion, driven by the US, EU, and UK, aimed to secure

geopolitical leverage, control Black Sea trade, and curb Russia’s resurgence,

while provoking a Russia-Iran-China counter-axis.

Motives of Key NATO Players

United States: Hegemony, Containment, and Economic Gain

The US led NATO’s expansion to cement its post-Cold War unipolar dominance.

Declassified documents from the Clinton administration reveal plans to

integrate Eastern Europe to prevent Russian revival (National Security Archive,

1997). Fiona Hill, a former US intelligence officer, notes, “The US saw NATO as

a tool to project power, ensuring no rival could challenge its European

influence” (Hill, 2022). Missile defense systems in Poland (2016) and Romania

(2019) underscored this, despite Russian objections. Dmitri Trenin observes,

“These systems, sold as defensive, were perceived in Moscow as a direct threat”

(Trenin, 2018).

Economically, the US targeted Russia’s energy dominance. By

promoting LNG terminals in Poland and Lithuania and the Southern Gas Corridor

(2020), the US reduced Europe’s reliance on Russian gas, which once accounted

for 40% of EU imports. Daniel Yergin states, “The US weaponized energy markets

to weaken Russia’s economic grip” (Yergin, 2021). Defense giants like Lockheed

Martin and Boeing profited, as new NATO members spent billions on US weapons to

meet standards. Noam Chomsky critiques, “NATO’s expansion is a boon for

corporate America, cloaked in security rhetoric” (Chomsky, 2018). Sanctions

post-2014 Crimea and 2022 Ukraine invasions further squeezed Russia’s economy,

targeting its $100 billion annual energy exports. Angela Stent argues,

“Sanctions were as much about economic warfare as punishing aggression” (Stent,

2020).

European Union: Stability, Markets, and Energy

Diversification

EU states, particularly Germany and France, supported NATO’s expansion to

stabilize Eastern Europe and expand economic influence. Joseph Nye explains,

“NATO provided the security framework for the EU to integrate Eastern Europe

economically” (Nye, 2019). Poland’s GDP, for instance, grew from $170 billion

in 1999 (NATO entry) to over $800 billion by 2025, driven by German and French

investments in automotive and energy sectors. Yanis Varoufakis critiques, “The

EU’s eastward push was about capital penetration, not just democracy”

(Varoufakis, 2021).

Energy was pivotal. The EU’s REPowerEU plan (2022) and Green

Deal (2020) aimed to shift Eastern Europe to renewables and LNG, reducing

Russia’s gas leverage. Anne Applebaum notes, “Europe’s energy pivot was a

geopolitical maneuver to sideline Russia” (Applebaum, 2023). The Southern Gas

Corridor, bypassing Russia, delivers Caspian gas to Europe, benefiting firms

like BP. Ukraine’s agricultural wealth (10% of global wheat exports) and shale

gas potential also drew EU interest. Maria Shagina states, “The EU’s economic

strategy in Ukraine aligns with NATO’s security goals” (Shagina, 2022).

However, Germany’s initial reliance on Nord Stream pipelines sparked tensions,

as Ivan Krastev observes: “Germany’s energy deals with Russia exposed EU

divisions” (Krastev, 2020).

United Kingdom: Transatlantic Bridge and Economic

Opportunities

Post-Brexit, the UK leaned on NATO to maintain European relevance. It trained

Ukrainian forces through Operation Orbital (2015–2022) and led Black Sea naval

exercises with Romania and Turkey. Robin Niblett states, “The UK used NATO to

counter Russia and secure its post-Brexit role” (Niblett, 2020). UK defense

firms like BAE Systems profited from Eastern European arms purchases, while

London’s financial sector backed regional infrastructure. Timothy Garton Ash

notes, “The UK’s sanctions on Russian oligarchs were strategic, aiming to

cripple Moscow’s economic base” (Ash, 2022).

Energy played a role, with the UK supporting LNG

infrastructure in Poland and anti-ship missile supplies to Ukraine, bolstering

Black Sea access. Rory Stewart argues, “The UK’s Black Sea strategy aligns with

US goals to limit Russia’s maritime trade” (Stewart, 2023). The UK’s alignment

with US sanctions further isolated Russia economically, redirecting trade

opportunities to Western firms.

Energy Markets and Geopolitical Linkages

Energy markets are a linchpin of NATO’s strategy and

Russia’s response. Pre-2022, Russia supplied 40% of Europe’s gas, earning $100

billion annually. NATO’s expansion disrupted this through diversification. The

US-backed Southern Gas Corridor and LNG terminals in Poland, Lithuania, and

Croatia reduced Europe’s dependence to under 10% by 2025. Daniel Yergin

explains, “The Black Sea became an energy battleground, with NATO and Russia

vying for control” (Yergin, 2021). Ukraine’s potential NATO membership threatens

Russia’s grain and oil exports via Odesa, as Michael Kofman notes: “Black Sea

ports are as much economic as military assets” (Kofman, 2023).

Russia’s 2014 Crimea annexation secured its Sevastopol naval

base, countering NATO’s presence in Romania and Bulgaria. The EU’s Green Deal

and REPowerEU prioritize renewables, further sidelining Russian fossil fuels.

Brenda Shaffer argues, “Europe’s renewable push is a geopolitical tool to

diminish Russia’s energy clout” (Shaffer, 2022). Meanwhile, the

Russia-Iran-China axis counters with alternative energy routes. Russia’s Power

of Siberia pipeline (2019) and $100 billion oil exports to India (2023) reflect

this pivot. Iran’s $400 billion China deal (2021) boosts its oil exports, while

China’s BRI invests in Black Sea ports like Georgia’s Anaklia. Pepe Escobar

states, “This axis is forging an energy and trade network to bypass Western

sanctions” (Escobar, 2023).

Propaganda Themes: Democracy, Aggression, and Narrative

Wars

NATO’s expansion was sold as a defense of democracy against

Russian authoritarianism. Antony Blinken claimed, “NATO’s open door is about

sovereign choice, not aggression” (Blinken, 2021). This narrative justified

1999 and 2004 expansions, despite Russian protests. Mearsheimer counters, “The

democracy rhetoric masks a power grab” (Mearsheimer, 2022). Post-2014, NATO

amplified Russia’s “aggressive threat” after Crimea and Ukraine, rallying

public support. Anne Applebaum observes, “Portraying Russia as a rogue state

fueled NATO’s expansionist momentum” (Applebaum, 2020).

Russia’s propaganda paints NATO as an imperialist aggressor.

Dmitry Medvedev declared, “NATO’s expansion threatens Russia’s sovereignty”

(Medvedev, 2022). This narrative resonates in Russia, framing the West as

encircling a victimized nation. Mary Dejevsky notes, “Both sides’ propaganda

creates a cycle of mistrust, escalating tensions” (Dejevsky, 2023). Stephen

Walt adds, with a wry nod, “NATO and Russia play the same game—noble ideals

hiding naked ambition” (Walt, 2021). The irony lies in both sides’ selective

truths: NATO’s “defense” enables economic control, while Russia’s “sovereignty”

justifies aggression.

Russia-Iran-China Axis: A Counterforce

The Russia-Iran-China axis emerged to counter NATO’s

expansion and Western sanctions. Russia’s pivot to Asia, accelerated post-2022,

saw China become its top trade partner ($240 billion in 2024). Iran’s drone

supplies to Russia and SCO membership (2023) deepened military ties. China’s

BRI competes with EU investments, targeting Eastern European markets. Alicia

Garcia-Herrero states, “China’s economic push challenges NATO’s regional

monopoly” (Garcia-Herrero, 2022). Trita Parsi argues, “This axis is a pragmatic

alliance against Western hegemony” (Parsi, 2023).

The axis counters NATO’s Black Sea dominance through trade

and energy deals. Russia’s Crimea control and China’s Georgian port investments

challenge Western access. Dmitri Trenin warns, “Russia’s alignment with China

risks long-term dependency” (Trenin, 2022). Yet, as Ankit Panda notes, “China’s

cautious support for Russia balances economic gain with avoiding Western

backlash” (Panda, 2023). This axis reshapes global alignments, countering

NATO’s economic and strategic moves.

Credible Defensive Reasons vs. Economic Motives

NATO’s defensive rationale strengthened after Russia’s 2008

Georgia invasion and 2014/2022 Ukraine actions. Fiona Hill states, “Russia’s

aggression made NATO membership a necessity for Eastern Europe” (Hill, 2023).

However, in the 1990s, Russia’s economic collapse posed little threat,

suggesting proactive motives. Stephen Cohen argued, “Early NATO expansion

filled a power vacuum, not a security gap” (Cohen, 2017). Economic

motives—energy control, defense profits, market access—are evident. Jeffrey

Sachs notes, “The West’s economic warfare, disguised as security, reshaped

global markets” (Sachs, 2023).

Russia’s counter-axis with Iran and China reflects its

response to economic strangulation. Pepe Escobar observes, “Russia’s Asian

pivot is its lifeline against NATO’s chokehold” (Escobar, 2022). The Black Sea

remains a flashpoint, with NATO’s diversification and Russia’s trade rerouting

fueling rivalry. As Richard Sakwa argues, “NATO’s expansion created the very

threats it claims to counter” (Sakwa, 2021).

Philosophical Take

NATO’s eastern expansion and the Russia-Iran-China axis

reflect a timeless struggle over power, sovereignty, and human aspiration. This

contest, cloaked in ideals—democracy versus sovereignty—reveals a deeper truth:

nations prioritize self-interest over shared humanity. Thucydides’ maxim, “The

strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must,” echoes here.

NATO’s expansion, sold as protection, asserts Western dominance, encircling a

weakened Russia. As Mearsheimer’s realism predicts, this provoked a

counter-axis, trapping both sides in a security dilemma where fear fuels

escalation. The irony is stark: NATO’s “defensive” moves ignite the threats it

claims to deter, while Russia’s “sovereign” resistance justifies aggression

that alienates its neighbors.

Energy markets—gas pipelines, LNG terminals, Black Sea

ports—symbolize this struggle for control. The West’s diversification, as

Yergin notes, is as geopolitical as economic, sidelining Russia while enriching

Western firms. Yet, Russia’s pivot to China and Iran, per Escobar, builds an

alternative order, not a moral one. Hannah Arendt’s lens reveals the danger:

propaganda, whether NATO’s democratic crusade or Russia’s victim narrative,

erodes truth, fostering cynicism. Both sides manipulate ideals to justify

ambition, leaving publics polarized and trust shattered.

This raises a philosophical question: Can humanity transcend

this Hobbesian trap? Kant’s vision of perpetual peace through cooperation seems

utopian when pipelines dictate strategy. Yet, the interdependence of global

systems—energy, trade, climate—demands a new paradigm. The Russia-Iran-China

axis, born of necessity, challenges Western hegemony but risks replicating its

flaws: power over principle. As Sartre might argue, nations face an existential

choice: cling to zero-sum rivalries or embrace mutual survival. The tragedy

lies in our failure to imagine a world where security is collective, not

competitive.

The Black Sea, a microcosm of this struggle, reflects our

shared fragility. NATO’s ports and Russia’s bases are not just strategic assets

but symbols of a divided planet. A philosophical shift is needed—one where

reason, not pride, guides policy. Dialogue, not demonization, could unlock

shared economic gains. As Camus wrote, “We must mend what has been torn apart.”

The path forward lies in recognizing our common humanity, lest we doom

ourselves to endless cycles of rivalry where power overshadows the potential

for peace.

References

- Applebaum,

A. (2020). The Atlantic. “Russia’s Threat to the West.”

- Applebaum,

A. (2023). Foreign Affairs. “Europe’s Energy Pivot.”

- Blinken,

A. (2021). US State Department Press Release.

- Chomsky,

N. (2018). Who Rules the World? Metropolitan Books.

- Cohen,

S. (2017). War with Russia? Hot Books.

- Dejevsky,

M. (2023). The Spectator. “NATO and Russia’s Propaganda War.”

- Escobar,

P. (2022). Asia Times. “Russia’s Asian Pivot.”

- Escobar,

P. (2023). The Cradle. “The New Eurasian Axis.”

- Garcia-Herrero,

A. (2022). Bruegel. “China’s Economic Push in Europe.”

- Hill,

F. (2022). Brookings. “NATO’s Strategic Imperative.”

- Hill,

F. (2023). Foreign Policy. “Russia’s Threat and NATO’s Response.”

- Kofman,

M. (2023). War on the Rocks. “Black Sea Geopolitics.”

- Krastev,

I. (2020). Journal of Democracy. “Europe’s Russia Dilemma.”

- Mearsheimer,

J. (2014). Foreign Affairs. “Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s

Fault.”

- Mearsheimer,

J. (2022). The National Interest. “NATO’s Expansion Folly.”

- Medvedev,

D. (2022). TASS News Agency.

- National

Security Archive. (1997). “Clinton Administration NATO Documents.”

- Niblett,

R. (2020). Chatham House. “UK’s Post-Brexit NATO Role.”

- Nye,

J. (2019). Soft Power and Global Politics. Harvard University

Press.

- Panda,

A. (2023). The Diplomat. “China’s Russia Strategy.”

- Parsi,

T. (2023). Responsible Statecraft. “Iran’s Role in the New Axis.”

- Sachs,

J. (2022). Consortium News. “NATO’s Geopolitical Agenda.”

- Sachs,

J. (2023). Common Dreams. “Economic Warfare and NATO.”

- Sakwa,

R. (2021). Frontline Ukraine. I.B. Tauris.

- Shaffer,

B. (2022). Energy Politics. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Shagina,

M. (2022). Carnegie Endowment. “Energy as a Geopolitical Tool.”

- Stent,

A. (2020). Putin’s World. Twelve Books.

- Stewart,

R. (2023). Foreign Policy. “UK’s Black Sea Strategy.”

- Trenin,

D. (2018). Carnegie Moscow Center. “Russia and NATO’s Missiles.”

- Trenin,

D. (2022). Carnegie Moscow Center. “Russia’s China Dependency.”

- Varoufakis,

Y. (2021). Another Now. Melville House.

- Walt,

S. (2021). Foreign Policy. “Propaganda and Power.”

- Yergin,

D. (2021). The New Map. Penguin Books.

Comments

Post a Comment